DNA Methylation Profiles and Placental Malaria

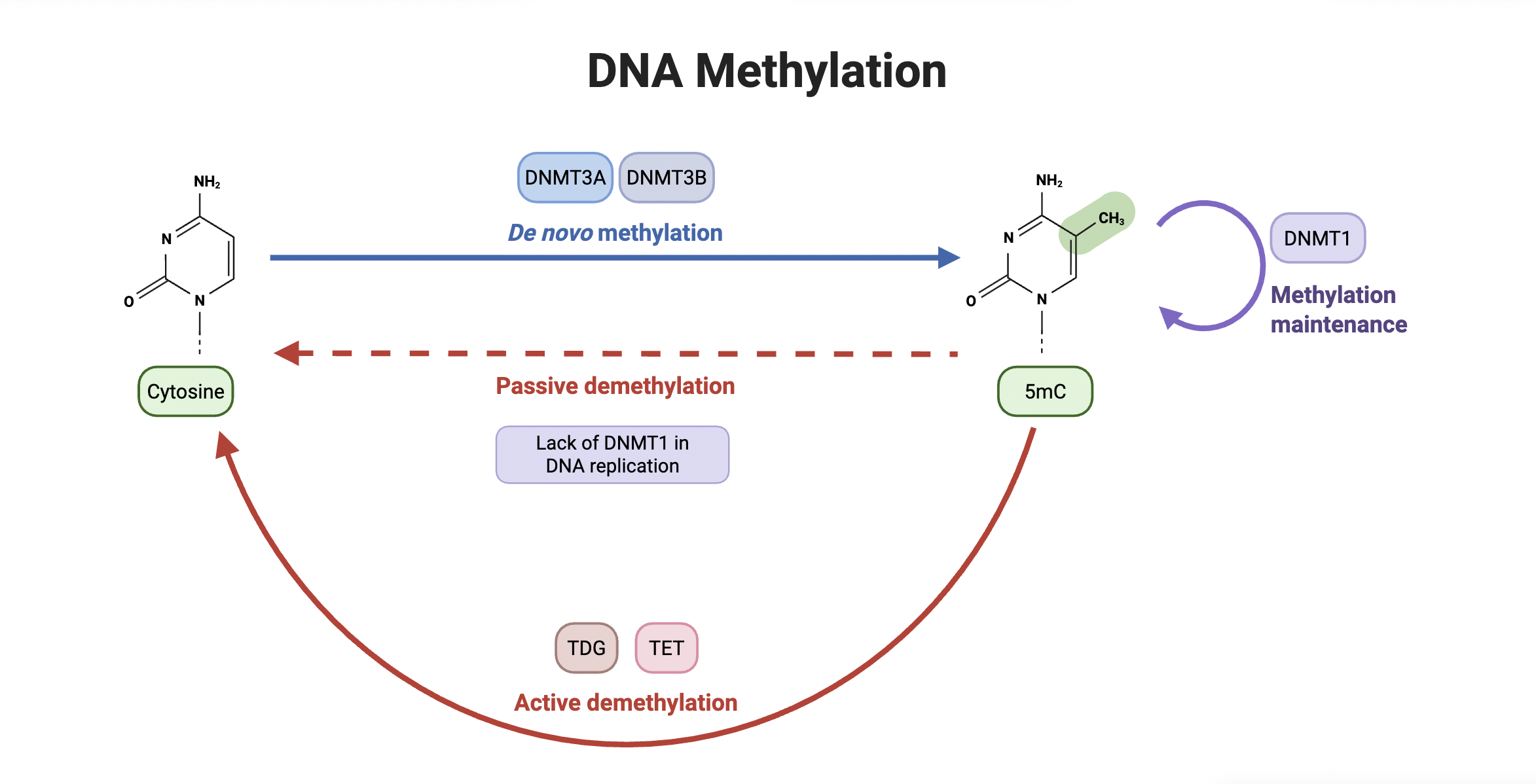

De novo DNA methylation is the process by which new DNA methylation patterns are established on previously unmethylated DNA. It occurs when the enzymes DNMT3A and DNMT3B add a new methyl group to cytosine, converting the compound into 5-methylcytosine (5mC). Demethylation, on the other hand, describes the removal of methyl groups from cytosine, occurring either actively through the involvement of TDG and TET enzymes or passively due to a lack of DNMT1, an enzyme responsible for maintaining methylation on a 5mC compound.

Written by Neha Lozano, Schematic by Lexi Bean

Placental malaria, a condition that can develop during pregnancy, is the leading global cause of fetal growth restriction (known as FGR for short) in babies and occurs when infected red blood cells accumulate in the placenta, blocking blood flow and nutrient distribution. This leads to inflammation and hinders the baby’s ability to grow. Though it most commonly stems from placental issues, FGR can also develop due to habits like heavy smoking or diseases like gestational diabetes.

In this article by Stephanie L. Gaw, Nida Ozarslan, et al., researchers studied DNA methylation patterns, and how they differed in cases of FGR that were and weren’t caused by malaria. DNA methylation patterns refer to the specific areas where methyl groups attach themselves to DNA, impacting the development and differentiation of cells. They are classified as epigenetic changes, which are modifications made to DNA that impact gene expression while leaving gene sequences (the order in which genes are placed on DNA strands) untouched. DNA methylation patterns are very sensitive to outside influences, causing them to change significantly in the event of infection, chronic stress, or chemical exposure. This can result in undesired changes that negatively affect the body.

To study this, the team utilized placental samples from two cohorts: pregnant women seen at UCSF Medical Center in California and in Busia, Uganda. Samples from UCSF were from cases of non-malarial FGR, while malaria triggered FGR in the samples from Uganda. Researchers also collected and analyzed normal, healthy placental samples – from pregnancies in which FGR did not occur – from both sites.

After extracting sample DNA, they conducted a series of comparisons to find similarities within the methylation patterns of the types of FGR. They focused on analyzing specific sites called CpG sites, regions in DNA where methylation most commonly occurs. Here’s how they did it:

1) They analyzed samples in individual groups: US controls, Uganda controls, US non-malarial FGR, and Uganda malarial FGR. However, they didn’t see significant differences in methylation patterns. When they instead compared samples in two general groups, normal FGR and placental malaria FGR, they noticed more CpG sites with differing methylation profiles.

2) Next, as a precaution, they analyzed how the respective geological locations of the control and FGR samples possibly impacted their methylation profiles. They pinpointed 65 different CpG sites where DNA methylation levels differed significantly between the control and non-malarial FGR samples. These 65 sites were located near genes responsible for nutrient transport and stress response. When comparing the Ugandan samples of malarial FGR to their controls, researchers found 133 CpG sites of interest, located near genes responsible for cell signaling or specialization.

3) They then compared the sets of CpG sites identified in malarial FGR and non-malarial FGR. While doing so, the team found that both cases shared a singular common hypomethylation CpG site, located in a unique region near the BMP4 gene. This gene is involved in various developmental processes, such as bone/cartilage formation and limb development, and plays a role in regulating cell processes. These findings indicated that cases of FGR both induced and not induced by malaria possess vastly different epigenetic profiles, only sharing one specific and targeted methylation change.

4) Following this discovery, the researchers directly compared the overall methylation profiles of the cases of FGR that were and weren’t caused by malaria to check again for epigenetic similarities. After careful analysis, researchers were able to attribute the differentiation of 7 common CpG sites to be caused by geographical conditions and shifted their focus to a group of 522 CpG sites associated with placental malaria.

After analyzing these 522 sites, they were able to conclude that non-malarial FGR and placental malaria FGR are epigenetically different. While many of the methylated genes in the non-malarial FGR cases were involved in a network of proteins that work to determine cell shape and enable cell movement, most methylated genes in malarial FGR were directly related to genes involved in organism development, nervous system process, and growth factor response. Based on the data collected and their analyses, researchers were able to discover that both cases of FGR were biologically distinct with different root causes and effects.

Thanks to the types of experiments they conducted, researchers were able to deduce the locations, related genes, and functions of the most significant and relevant CpG sites. These sites and this information will likely play a crucial role in the creation of successful therapies and other useful medical interventions for patients suffering from or at risk of developing these conditions. The data collected in these experiments is also vital in understanding what specific effects each type of FGR may have on babies if diagnosed and is very helpful when developing more efficient treatment plans. In all, this project provides us with a better understanding of fetal growth reduction in babies, as well as new insights into designing more optimal and effective care for those affected by this condition.

A link to the publication can be found here: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15592294.2025.2475276#abstract