Are Gut Microbes “Eating” Your Peanut Allergy Treatment?

This study provides a more comprehensive and in-depth secondary analysis of the IMPACT clinical trial that was published in 2022. In the IMPACT trial, children aged 1 to 4 years old who were allergic to peanuts were randomly treated with either POIT (peanut) or a placebo (oat flour). For two years, the researchers collected their stool (poop) samples at five different time points, from before the treatment to weeks after ending the treatment. In this way, they created a “history book” of the gut microbiome along the progression of POIT (Jones et al., 2022). The study from the Lynch Lab read this “book” and mainly focused on poop samples from the POIT-treated children, using various advanced methods to analyze the bacteria found within.

Written by Scarlett Yang, Schematic by Lexi Bean

What is the study about?

Peanuts, though delicious and nutritious, are one of the most common causes of food allergies, affecting 1-2% of the U.S. population. The allergic reactions can be severe and acute, including swelling in the larynx (voice box), persistent coughing, vomiting, diarrhea, arrhythmia (abnormal heart rhythm), and many others (Burks, 2008).

Acute symptoms are a consequence of the immune system’s response to specific proteins in peanuts, known as Ara h proteins. These proteins enable the peanut seed to store nutrients (Singh et al., 2021). However, some people’s immune system mistakenly perceives them as threats and activates multiple lines of defense, including the generation of specialized security guards - antibodies. The antibodies then send out alerts and trigger subsequent allergic reactions.

For many years, the main approach to “treat” these symptoms was to try to avoid them - i.e., to avoid any food with peanuts. Fortunately, a more robust treatment called peanut oral immunotherapy (POIT) was approved for clinical use in 2020 (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2024). The goal of this therapy is to facilitate desensitization (reducing the response to a stimulus after prolonged or repetitive exposure). This is a bit similar to slowly increasing muscle strength: the treatment starts with a tiny amount of peanut powder and gradually increases the dose (weight). It is highly effective in 50-70% of patients (mainly preschool children, as POIT hasn’t been studied extensively in adults) and has become the most widely used therapy for peanut allergy. This change represents a revolution in care for allergies, where people who were deadly allergic in a previous generation, carrying the stress of peanut encounters and epinephrine “epi” pens, can now be typical consumers of nutty things.

Though POIT desensitizes the vast majority of patients to peanut allergens, 70-80% of patients fail to achieve “remission.” That is to say, allergic reactions to peanuts recur without treatment. To be allergy-free to peanuts for an entire life, the patient may have to receive continued POIT or exposure to peanut dosing regularly. This time commitment and high cost of POIT are too high for many patients, especially when the patient is still of preschool age!

With an urgent need to reduce the lifelong impact of peanut allergies, scientists from the Lynch Lab at UCSF started to look for the reason behind the failure of this treatment, trying to figure out why its effect only lasts for a long time in some patients but not others. Led by Dr. Mustafa Özçam, who was a postdoctoral researcher in the Lynch Lab and is currently an assistant professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, their research was published in Nature Communications this year, revealing revealed crucial links between the gut microbiome (the ecosystem of microbes in the gut), a type of digestive chemical called bile acid, and POIT failure.

How was the study conducted?

This study provides a more comprehensive and in-depth secondary analysis of the IMPACT clinical trial that was published in 2022. In the IMPACT trial, children aged 1 to 4 years old who were allergic to peanuts were randomly treated with either POIT (peanut) or a placebo (oat flour). For two years, the researchers collected their stool (poop) samples at five different time points, from before the treatment to weeks after ending the treatment. In this way, they created a “history book” of the gut microbiome along the progression of POIT (Jones et al., 2022). The study from the Lynch Lab read this “book” and mainly focused on poop samples from the POIT-treated children, using various advanced methods to analyze the bacteria found within.

16S rRNA (ribosomal RNA) sequencing - Who’s there? Each type of bacteria has a unique ribosomal RNA gene - i.e., 16S rRNA - that distinguishes it from other bacteria. By examining these unique 'name tags', researchers identified which bacteria were in the gut and whether the composition of the bacterial community changed over time between POIT responders and non-responders.

Shotgun metagenomics - What can they do? Since 16S rRNA sequencing is based on a single gene, it cannot tell the functions and gene content of the entire microbiome. Thus, to determine what the bacteria do, the researchers used shotgun metagenomics. By sequencing all the DNA in the samples, this method allowed for identifying specific functional genes, such as those responsible for making enzymes. This provides a bigger picture of what the bacterial communities in the gut are capable of.

Untargeted metabolomics - What do they produce? Metabolomics studies metabolites, or the small molecules produced by the gut bacteria during their metabolism. Researchers traced and analyzed these chemicals to study the metabolic activity of the gut microbiome during POIT.

Fecal microbiome culture: To confirm whether the gut bacteria could “eat” peanut proteins, the researchers incubated the children’s fecal samples with peanut extract in the lab. After 48 hours, they measured the concentration of the Ara h 2 protein to determine how much had been metabolized.

What did they discover?

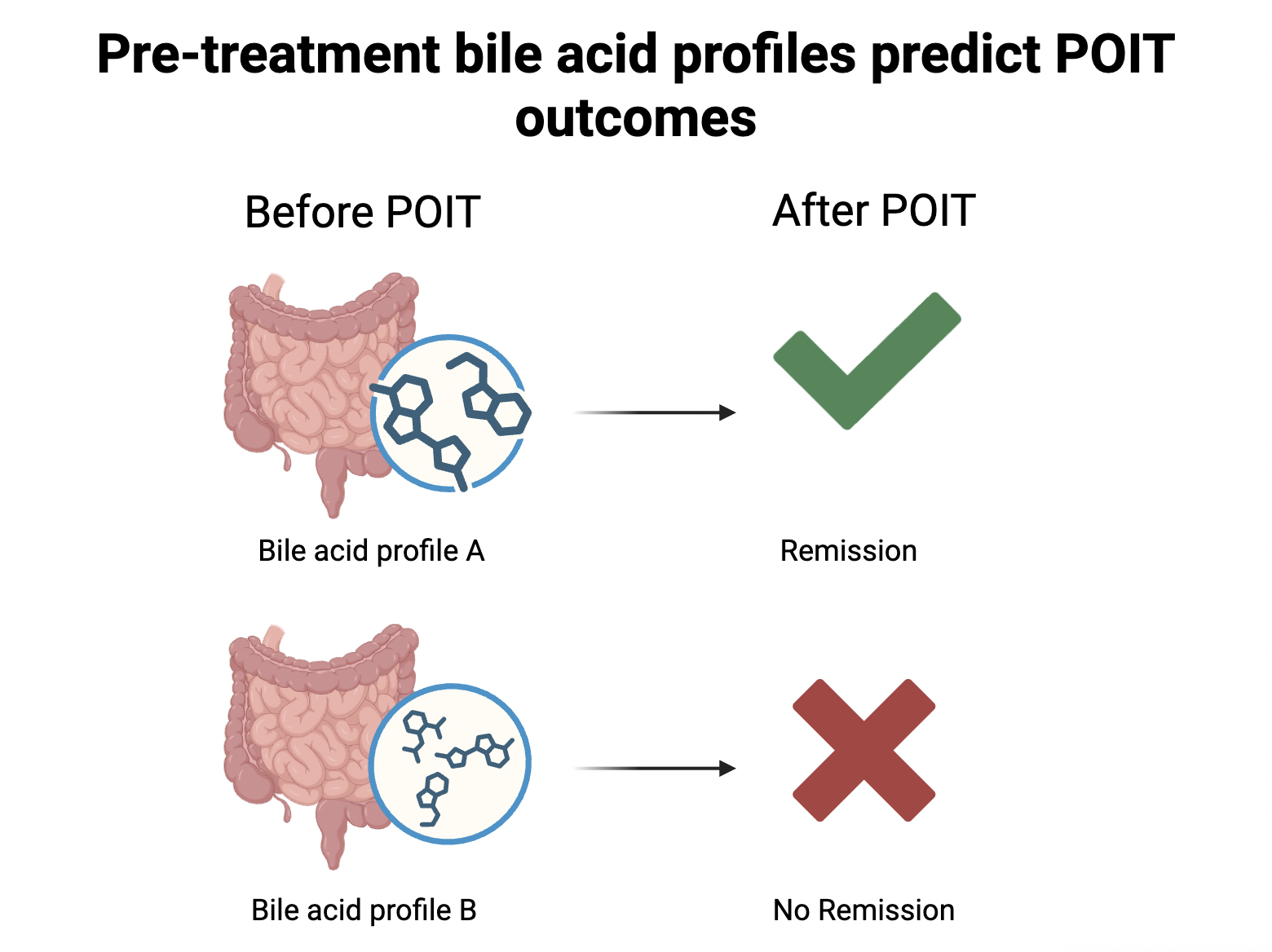

Pre-treatment bile acid levels predict POIT outcomes: In the study, the researchers found a distinct bile acid profile in children who successfully achieved remission. In these children’s gut, certain types of bile acids and their modified forms, including 7-ketodeoxycholate and 7-ketolithocholate, were found to be more or less abundant before POIT even started. Further analysis revealed that this level difference was driven by the population difference in the children’s gut bacteria. For instance, the successful patients hosted a larger number of microbes, including Bifidobacterium breve and Ruminococcus gnavus. These bacteria produce enzymes needed for the metabolism of certain bile acids, thus increasing the level of the bacteria-modified form of those bile acids (also known as secondary bile acids).

Bile acids are chemicals that help with fat digestion. They are first produced in the liver and then transported to the gut, playing a crucial role in breaking down the hamburger one might just have for lunch. Surprisingly, the study discovers that they are also associated with responses to POIT. The level of bile acid in the gut before the treatment may be used to predict whether the patient will achieve remission. Or, in other words, whether the treatment effect can last after POIT ends.

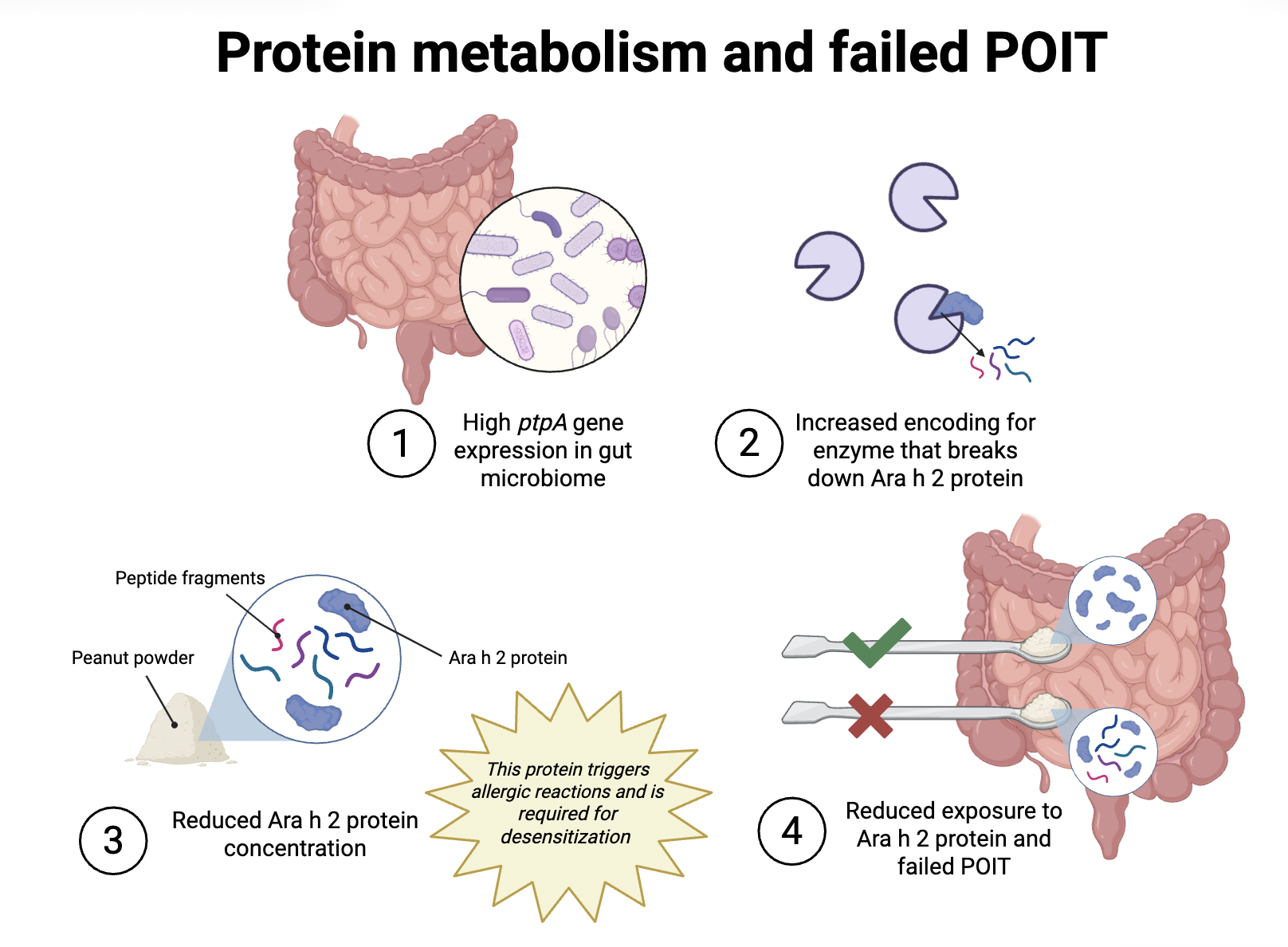

2. The gut bacteria are “eating” the proteins in the treatment: Though bile acid profiles can be good predictors for POIT failure, they do not explain why or how POIT failure happens. To learn about the underlying mechanism for POIT failure, the researchers turned to look at another clue: amino acids (the “building blocks” of proteins) in the gut. After noticing a lower concentration of amino acids in the children who failed to achieve remission, they started to connect protein metabolism by the gut microbiome with POIT outcomes.

It turned out that the gut bacteria of the children who did not develop POIT-induced remission had a larger number of the ptpA gene. This ptpA gene codes for a type of enzyme (proteins that speed up biological reactions) that can chop up Ara h 2 proteins. Thus, gut bacteria with more of this gene produce more enzymes that can break down Ara h 2 proteins. In other words, these bacteria are “hungrier” and eat up the Ara h 2 proteins. This sabotages the POIT as the immune system is prevented from learning to adapt to the exposure to Ara h 2 proteins.

3. Higher gut microbiome diversity is related to POIT failure: This study also shows that children with higher gut microbiome diversity are more likely to fail POIT. This correlation may seem counterintuitive, given that a higher diversity is generally considered to be related to better health. But in the context of food allergies, a high gut microbial diversity isn’t always better. Previous research shows that a higher microbiome diversity, though beneficial for infants, usually becomes a risk factor for food allergies and asthma in older kids (Shenhav et al., 2024). This pattern is consistent with the findings of this study. Furthermore, the study provides explanations for why such a correlation occurs: the features in bile acid and amino acid metabolism are linked to higher microbial diversity. Specifically, the bacterial species participating in processing certain bile acids and degrading amino acids tend to be more abundant in children who fail POIT.

Why does it matter?

The findings of this study could affect clinical practice in two key ways. First, the study may provide a new biomarker to predict POIT outcomes. This may help patients decide whether to receive POIT before they start. So far, patients go into POIT without knowing whether they will have a lasting therapeutic effect. However, this study may be a game-changer as it offers the bile acid profile that identifies the candidates who will more likely achieve long-term remission. Simply by testing the levels of different types of bile acids in fecal samples, doctors may be able to give patients more information about the possible treatment outcomes and help some of them avoid unnecessary time and cost.

Second, by revealing the mechanism behind POIT failure, the research informs future improvements in POIT. Now we have learned that for the patients where POIT fails, their gut bacteria are “hungrier” and eat up peanut proteins before the immune system even gets to recognize and tolerate them. With this knowledge, scientists may improve the current treatment by targeting the gut microbiome’s metabolic ability. For instance, they may protect the peanut proteins used in the therapy in bioavailable capsules so the proteins do not get metabolized by the gut bacteria, but can train the immune system instead. Or, some substances like probiotics can be prescribed adjunctively to modulate the metabolic activity or composition of the gut microbiome, aiming to achieve the desired therapeutic effect in the long run.

A link to the publication can be found here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-61161-x

References

Burks, A. W. (2008). Peanut allergy. The Lancet, 371(9623), 1538–1546. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60659-5

Jones, S. M., Kim, E. H., Nadeau, K. C., Nowak-Wegrzyn, A., Wood, R. A., Sampson, H. A., Scurlock, A. M., Chinthrajah, S., Wang, J., Pesek, R. D., Sindher, S. B., Kulis, M., Johnson, J., Spain, K., Babineau, D. C., Chin, H., Laurienzo-Panza, J., Yan, R., Larson, D., … Burks, A. W. (2022). Efficacy and safety of oral immunotherapy in children aged 1–3 years with peanut allergy (the Immune Tolerance Network IMPACT trial): A randomised placebo-controlled study. The Lancet, 399(10322), 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02390-4

Özçam, M., Lin, D. L., Gupta, C. L., Li, A., Gomez, J. C., Wheatley, L. M., Baloh, C. H., Sanda, S., Jones, S. M., & Lynch, S. V. (2025). Gut microbial bile and amino acid metabolism associate with peanut oral immunotherapy failure. Nature Communications, 16(1), 6330. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61161-x

Shenhav, L., Fehr, K., Reyna, M. E., Petersen, C., Dai, D. L. Y., Dai, R., Breton, V., Rossi, L., Smieja, M., Simons, E., Silverman, M. A., Levy, M., Bode, L., Field, C. J., Marshall, J. S., Moraes, T. J., Mandhane, P. J., Turvey, S. E., Subbarao, P., … Azad, M. B. (2024). Microbial colonization programs are structured by breastfeeding and guide healthy respiratory development. Cell, 187(19), 5431-5452.e20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.07.022

Singh, A., Raina, S. N., Sharma, M., Chaudhary, M., Sharma, S., Rajpal, V. R., Singh, A., Raina, S. N., Sharma, M., Chaudhary, M., Sharma, S., & Rajpal, V. R. (2021). Functional Uses of Peanut (<em>Arachis hypogaea</em> L.) Seed Storage Proteins. In Grain and Seed Proteins Functionality. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.96871

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2024). PALFORZIA. FDA. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/allergenics/palforzia