The Distinction between HIV and Obesity Related SAT Fibrosis

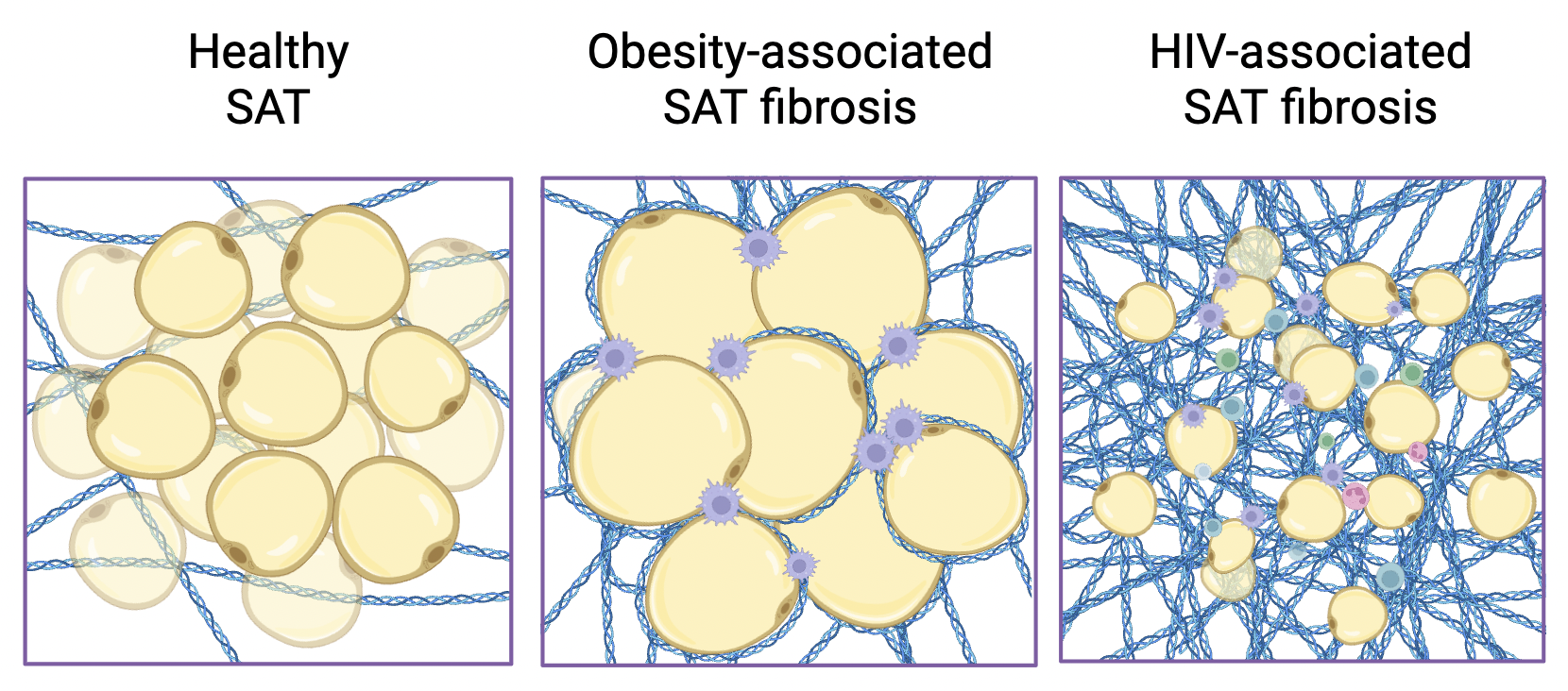

Subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) fibrosis is the buildup of fibrous tissue around fat cells under the skin. Common in obesity, this scarring can limit healthy fat storage and is linked to insulin resistance. Because people living with HIV have higher rates of metabolic complications, this figure compares healthy SAT, obesity-associated SAT fibrosis, and HIV-associated SAT fibrosis—illustrating how normal, round adipocytes become surrounded by thick collagen in obesity and replaced by dense fibrotic tissue in HIV.

Written by Michael He, Schematic by Lexi Bean

What is the study about?

Dramatic improvements in antiretroviral therapy (ART) have made it possible to suppress viral replication of HIV and, therefore, prevent the most serious consequences of HIV infection. Nonetheless, HIV remains a significant global health concern. One reason is that the continued presence of HIV can weaken the immune system and, in doing so, make the body more vulnerable to other infections and metabolic conditions such as type 2 diabetes.

People with HIV often develop insulin resistance and diabetes even if they aren’t overweight. This raises an important question: while obesity is a well-known cause of insulin resistance in the general population, what makes people infected with HIV develop these metabolic conditions?

To study the early drivers of insulin resistance, Dr. Diana Alba and scientists from the University of California, San Francisco focused on a condition known as subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) fibrosis. SAT is the fat stored under the skin, and when it becomes filled with too much fibrous tissue, it loses its ability to properly store and release energy. This buildup acts like a scar, disrupting fat function and contributing to diseases like diabetes.

The team wanted to know whether SAT fibrosis is different among people with HIV, or whether it follows the same pathway seen in obesity. This distinction is important because many health conditions share overlapping risk factors, making it difficult to determine whether a problem like insulin resistance is caused by obesity, HIV, or a combination of both.

How was the study conducted?

SAT can behave very differently from fat packed around the organs. Therefore, the researchers sought a way to measure fat beyond simple weight (BMI) and understand how fat is stored in the body. Using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) allowed the researchers to measure not just how much fat someone had, but also precisely where it was located in the body.

This study focused on 112 adults (43 people with HIV and 69 people without HIV). The researchers excluded type 2 diabetes patients because it would make it harder to tell whether the changes in fat tissue were due to HIV or just the result of having diabetes. The scientists measured levels of the amino acid hydroxyproline, a biomarker for SAT fibrosis as well as endotrophin, a protein piece released when tissue scarring occurs. Furthermore, the scientists used a targeted fibrosis-related gene panel to see how HIV infection and body fat levels influence gene activity.

What did they discover?

In the study, people with HIV had more fibrosis compared to people without HIV, with the largest differences observed among participants who were not obese. This suggests SAT fibrosis can cause insulin resistance separate from obesity in people with HIV.

The genetic analysis further supported this finding. A major discovery was an increase in COL14A1 in participants with HIV. This gene produces a collagen protein that helps form connective tissues, and its higher activity points to a unique scarring process in the fat tissue of people with HIV. This supports that SAT fibrosis in people with HIV is an HIV specific process, and not merely a consequence of excess body fat.

The researchers also discovered that endotrophin levels were higher in people with HIV and strongly linked to SAT fibrosis, showing promise as a non-invasive biomarker that could one day help doctors identify early metabolic risks without relying on biopsies. Finally, by measuring hydroxyproline in fat tissues, the researchers confirmed that genetic signals were not just abstract data, but are real, physical changes in the tissue. Increased hydroxyproline levels in people with HIV indicated SAT fibrosis disrupts metabolism.

Despite the findings, the study also had limitations. The group with HIV had a higher proportion of male and Black participants; findings in that population might not be representative of findings in other populations. Furthermore, the genetic analysis was limited to a fibrosis-focused gene panel, which might have excluded other relevant pathways.

Nevertheless, the study revealed that, contrary to what was previously and is often still believed, insulin resistance in people with HIV isn’t simply explained by being overweight or having excess body fat. Instead, it is closely tied to scarring in subcutaneous fat tissue- and this link shows up even in people who aren’t obese.

Why does it matter?

The results of the paper emphasize the lack of studies on the role of SAT fibrosis in metabolism among people with HIV. Previous research often lacked a proper control group of people without HIV, making it difficult to identify HIV-specific effects. By directly comparing people with and without HIV, this study made it possible to distinguish changes caused by HIV itself from those caused by obesity. The study further suggests that relying on weight or BMI alone isn’t enough to identify who is at risk. Instead, looking at fat tissue health — and especially fibrosis — may be a better indicator. Overall, the study provides a great foundation for future studies and adds to our body of knowledge on the effects of HIV.

A link to the full publication can be found here: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40463535/